An active hurricane season is likely ahead according to the two titans of the pre-season forecasting: warmer than average water temperatures and the arrival of La Niña. Those two are likely to work in tandem to create a busy season.

While it is too early to determine the exact number of tropical storms or hurricanes or where they might go this season, we can begin to take a qualitative look at how hurricane season may turn out.

To do this, we turn our attention to climate signals and to what defines a season.

Hurricane season is largely defined by when conditions are favorable for tropical development in the tropics. We say “largely” here because we can always get a renegade early-season (sub)tropical cyclone that goes against the conventional rules. We often have to wait for the jet stream to lift northward, for dry air and dust to clear out from the Atlantic and, most notably, water temperatures to warm up.

In recent years, however, we haven’t had to wait as long for the water temperatures to warm. And this year is another example.

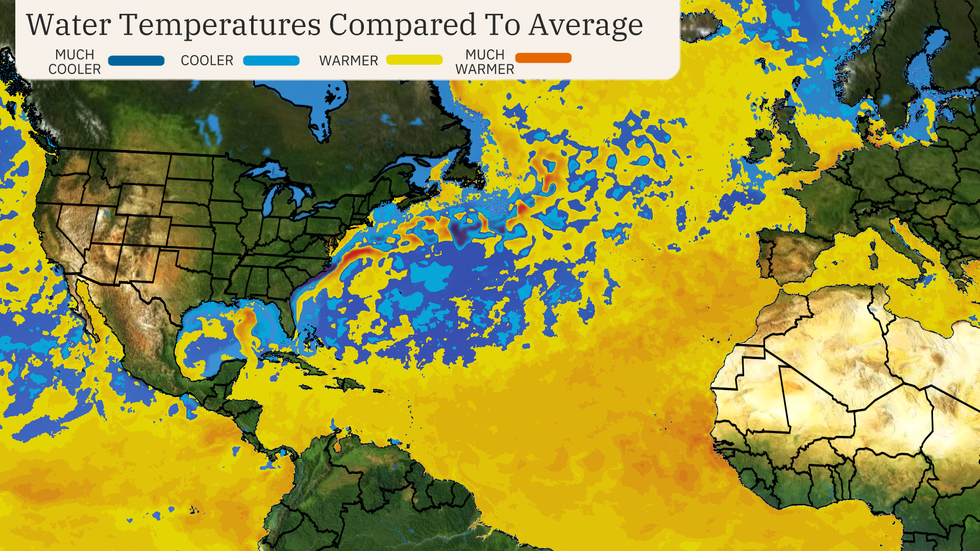

Water temperatures are record warm: Temperatures in the Main Development Region – the stretch of water between the Caribbean and Africa where the bulk of tropical development begins – are as warm in mid-February as they typically would be in June or July. That’s just a different way of saying that water temperatures are also warmer than they ever have been for this time of year.

No matter when the calendar says hurricane season is, it can begin early and last longer if water temperatures are above that rough 80-degree benchmark.

It is safe to say that if you look at water temperatures alone, hurricane season is already here.

Warm early-year sea surface temperatures are also predictive of warm water temperatures, weaker wind shear and lower pressures in the tropical Atlantic at the peak of hurricane season.

Later in the season, water temperatures can also dictate how many hurricanes there are and how strong they can get.

But for now, it’s also worth a look back at last hurricane season to suggest how 2024 may shake out.

In 2023, there was a lot of chatter about conflicting signals going into hurricane season. El Niño was expected to decrease the amount of tropical systems as well as the intensity of the systems that did form. What actually happened was that the very warm waters in the Atlantic won out and there were 20 named storms.

This year, it is unlikely that the fading El Niño will have any impact on the season.

La Niña likely by the peak of hurricane season: The latest outlook from NOAA says there is a 74% chance of water temperatures in the Pacific being cool enough to declare a La Niña for the peak of hurricane season (August through October).

La Niña typically suppresses wind shear in the Caribbean and also allows for more atmospheric instability across the basin. That instability leads to thunderstorm growth and can eventually lead to hurricane development. Trade winds can also relax in the Main Development Region, which allows tropical waves to take their time crossing the Atlantic, allowing them more time to fester and develop.

Last year’s result is important to note because those conflicting factors will now become factors working together should this flip to La Niña occur. La Niña typically does not cause the sinking air in the Caribbean that we saw last year. This should add up to the Atlantic being able to produce more tropical storms and hurricanes.

Climate change has a role to play, too: While climate change isn’t the only reason the number of tropical storms is increasing, it is the main driver behind storms getting stronger and intensifying more rapidly.

“The warmer ocean temperatures are contributing to our strongest hurricanes becoming stronger and at a faster rate. The number of category 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes are on the rise. The likelihood a storm will undergo rapid intensification, or when winds in a storm increase by approximately 35mph in 24 hours, is five times higher than it was in 1980,” weather.com meteorologist and climate expert Kait Parker said.

She adds that “another way of looking at the additional strength of our storms is Accumulated Cyclone Energy. ACE measures the wind energy output of anything stronger than a tropical storm. Storms in the Atlantic have contributed to higher ACE values in recent years, with 8 out of 10 of the top years happening in the 2000s. So while we may not be seeing more hurricanes, we can measure the higher energy output storms are having due to anthropogenic climate change through the increase in ACE values.”

Source: https://www.wunderground.com/article/storms/hurricane/news/2024-02-20-100-days-hurricane-season-la-nina